Who was the first European to visit Jefferson County and when? The answer usually given is George Logan in 1801. But exploration started the middle of the eighteenth century and perhaps earlier.

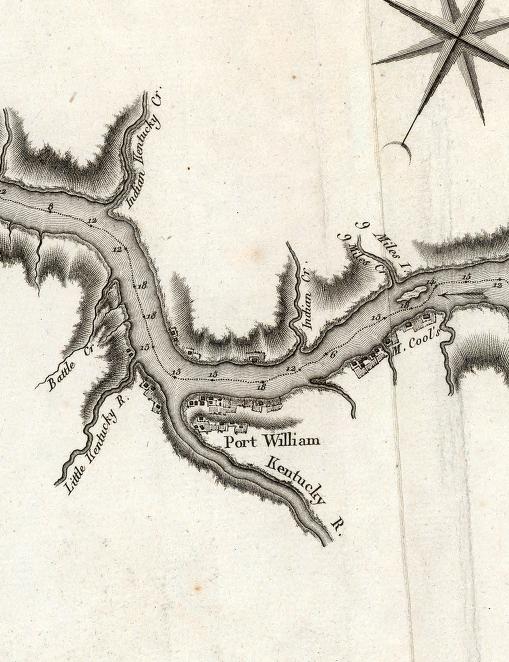

A crudely drawn map, referred to as the Trader’s Map, usually dated to 1753, shows a stream entering the Ohio at the right place for the Indian-Kentuck Creek. The creek that enters the Ohio River at Brooksburg. In 1778, Thomas Hutchens produced a more carefully drawn map which shows lines of latitude and longitude and shows what is almost certainly the Indian-Kentuck, although no streams were named. Given the map’s accuracy, someone must have gone up the creek to chart it.

The Indian-Kentuck became the first geological feature in Jefferson County to get an English name, when it appeared on John Filson’s first map of Kentucky, Drawn in 1784, and published in 1793, the stream was the only one on the Ohio river’s north shore between Cincinnati and Louisville to have a name.

The name was also used in an ordinance adopted by Congress on May 3, 1786, which establishing the creek as the western boundary of land to be surveyed. As Indian-Kentucky, it appeared again when a retired French General Victor Collot floated down the Ohio on a spying mission, and passed the area sometime after March 21, 1796, when his voyage began in Pittsburgh. Collot referred to three creeks between the Indian-Kentuck, which were not Hutchens’ map, implying that the Indian-Kentuck Creek was.

The name’s origin was explained by two visitors to the area, Fortescue Cummings, who toured the Midwest from 1807 to 1809, and David Thomas, who visited Madison 1816. Pioneers gave names to streams on the northern side of the Ohio by adding the words Indian in front of names of streams on the south side. So Wheeling Creek, Short Creek, and the Kentucky River, which flowed north, had counterparts called Indian Wheeling Creek, Indian Short Creek, and Indian-Kentuck Creek, which flowed south.

Europeans continued to visit the area with Kentucky settlers and Indians exchanging raids that brought them on the Indian side, opposite the mouth of the Kentucky River. One account identifies a settler named McMullen who was captured on the Indiana side on Feb. 13, 1790.

We can put another name to visitors the next year when General Charles Scott led 752 mounted men north to find Indians. Scott crossed the Ohio on May 23 and 24, 1791 at a place that was described as opposite the mouth of Battle Creek, five miles below the mouth of the Kentucky River. While the name is no longer used, a 1795 map shows that Battle Creek was the earlier name for Locust Creek in Trimble County.

Two years later, teenagers John and Peter Smock were captured by Indians in Shelby County, Ky., about 1793. The settlers pursued the Indians, who camped for three days on the site where the Jefferson County courthouse now stands, according to an 1874 account by their nephew John Smock.

A few years later, Indians complained to Gov. William H. Harrison that Europeans crossed the Ohio in search of game from the mouth of the Kentucky to the Mississippi and were depleting the Indians’ food. In a letter written in July 1801, he noted these expeditions occurred every fall.

So by the time George Logan carved his named into a tree near Hanover in 1801, a lot of European feet had set foot in Jefferson County.