Friday, November 13, 2009

Jefferson County's Many Presbyterian Churches

Sunday, August 2, 2009

Speaking Southern Hoosier: Names

And while much of the country terminology, some of it leftover from the Hoosier accent before the Kentucky accent crept north, is gone or dying, it's useful for genealogists, historians and the just curious as to how things were or are pronounced differently.

Other pronunciations that lingered in my family involved names. It took years before I found out that the "Old Doc Mathis place" near China had belonged to a Dr. Mathews. It's just that the name was pronounced Mathis into the late 1900s and it's a pronunciation that bedeviled census takers and later family historians who might not have realized that Mathis and Mathews were the originally the same name.

Then there is the name Banta, a name from the Frisian area of Holland and one of the families that was part of what was called the Low Dutch, such as the Rykers and Demarees. In my father's hands, it was "Bahn-tee" with the "a" pronounced like the "o" in the word bond and the second "a" converted to a "y" or "i" sound. And that Banty or Bonty spelling pops up in census records in the 1800s.

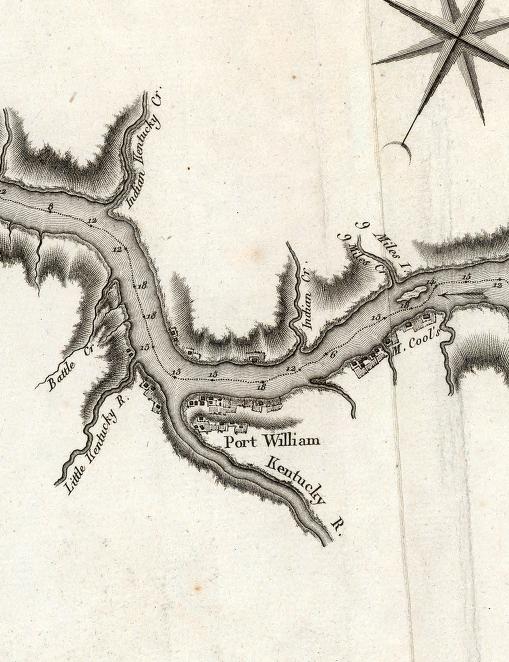

Likewise, the Stewart family name was rendered Steward by my parents. It took me years to realize the Steward bridge over the East Prong of the Indian Kentuck (where U.S. 62 crosses the creek) was spelled Stewart. In fact, that "d" ending harkens back to the original family occupation, when they were Sty-wards (pigkeepers) for Scottish royalty. And locally, Buchanan is not Byoo-kanan, but Buh kanan, a pronunciation that caused the name to be spelled Buckhanan or the like in many records.

Demaree got a different treatment. Instead of Dem-a-ree, my father pronounced it Dumb-a-ree. (No offense please) And that was probably a longstanding pronunciation as the 1840 census spells the name as Dumaree. While the Buchanan pronunciation is still common, the Dumb-a-ree is not. Also disappearing is Sibben-tal for Siebenthal, which is closer to the original German, but more often now, the last syllable has "thal" like the sound in think.

Among other names whose spelling reflected spoken spounds included Bondurant, rendered Bundren or Bundrent, Vernon, often written as Varnon (or worse) and Lewellyn, which often turned out as Lewallen. I can't say that I heard my family use these, but clearly they were not rare versions.

Saturday, July 25, 2009

Church Non History

"That's what the church says," was the response I got from a friend. It was that same week that I realized how often in writing church histories, writers neglect to read the church's own minutes.

For example, in the late 1900s, the claim began being made that the Indian-Kentuck Baptist Church was founded in 1812. The difference isn't terribly important, except that a statement written in the minutes said it was founded in 1814 (the minutes up to 1817 are missing). This was probably the same church history published by the Madison Association in 1860 and written by the church's long-time minister, Robert Stevenson.

Of course, written history can lead people astray. A History of Milton Township that was published around 1910 for the Jefferson County Historical Society and probably written by the group's president, William E. Ryker, said the Manville Christian Church grew out of the Manville Baptist Church.

The problem is that there is no record of a Manville Baptist Church. And all evidence points to Manville's growing out of the Milton Baptist Church which sat on the East Prong of the Indian-Kentuck Creek and operated 1829-1836 and 1840 until about 1880.

Annual minutes of meetings of the Coffee Creek Baptist Association, which covered Jefferson County during the second half of the 1820s, show no Manville Baptist Church. What they do show is that John Lanham and William Yates were messengers from Milton Baptist to the Coffee Creek Association meeting of Sept. 5, 1929, just after that church formed.

However, Manville Christian Church records show John Lanham was member No. 2 and William Yates member No. 4. Although this part of the list is undated, it appears members were listed as they joined and that the list dates to Manville's founding in 1830 and these two had jumped ship within a year of Milton's founding.

Back to the Madison Church. While it didn't directly originate in Mt. Pleasant, the real story is more remarkable.

Mount Pleasant voted to disband in April 1831 in order to promote the formation of a Baptist church in Madison and most members joined the newly formed Madison Baptist Church, which is clear from a biographical sketch of Mt. Pleasant's minister, Jesse Vawter.

But Madison had formed a building committee in June 1829 and on December 18 that year, a committee was organized to form a church. The charter members, and these dates, were in a sketch published in the 1869 minutes of the Madison Baptist Association.

And, oh yes, they are in the minutes of the Madison Baptist Church.

Monday, June 15, 2009

Madison and the International Pork Business

From the earliest days, Midwestern farmers had connections overseas because the only viable route for their products was the Ohio River, taking goods to New Orleans and sometimes beyond. In the footnotes of the book issued as the "History of Switzerland County", Perret Dufour reported how James Bolens went to New Orleans about 1822 and couldn't get a price he could accept and so took his pork cargo to Havana. Dufour also noted how Bolens spotted a threatening looking man in New Orleans, who he also spotted in the crowd in Cuba, suggesting there was a good bit of traffic between those cities.

An author named P.L. Simmons spelled out many of the practices of slaughtering and the market for pork products in an article entitled, "The Commercial Products of the Hog," which was published in the Journal of Agriculture in an issue dated July 1855-March 1857. He reported 38,164 barrels of pork were imported at Liverpool during the year ended Oct. 31, 1853, with 10,500 barrels originating in Canada and the United States. He noted that businesses that catered to the New York market did their slaughtering principally from October 1 to December 1 each year to avoid icing of waterways. Madison's season generally fit into this period.

Two court actions show how the shipping business worked. In 1850, there was an shipment that gave rise to a law suit (Josiah Lawrence vs. White and Stevens) in the U.S. Circuit Court regarding "A contract to deliver pork at Madison, in the State of Indiana, well put up, for the English market …" The pork was shipped to New Orleans and then to Baltimore, where it was received spoiled. The contract called for the delivery of 319 boxes of long middles of pork with the Cumberland cut, meaning part of the bone was left in. Each box contained seven or eight middles. The contract had called for 500 boxed, but that was reduced. That meant the original plan involved delivery of middles from more than 3,500 hogs. The defendants (presumably David White and Stephen Stevens) won their case, largely because the defendant found the pork in good order at Madison.

Even after its boom had passed, Madison was still involved in the international trade. Another Madison packer, Fitch & Son, squared off against City of Madison who assessed for pork as personal property in 1860 and 1861. The Indiana Supreme Court ruled against Madison. Noting many residents engaged in businesses shipping goods to New Orleans and to foreign markets it commented that the pork business could not be taxed.

"Filch & Son, during all that time, had no money or other personal property except their pork, all of which was for export, and was then in process of being exported to a foreign market." Those were key words for the court noted the Madison city charter, as amended in 1849, exempted produce held for export or in transit and found that the pork fit that definition.

Monday, May 25, 2009

Jefferson County's Records

After 40 years of studying them, I believe I know more about their contents than anyone as there are many types of records that I have not seen anyone else use, although I do not profess to be an expert on every record.

Nevertheless, wills, probate records, warranty deeds and marriage returns for the 1800s have been microfilmed and copies are available for viewing at several places, including the Madison-Jefferson County library. Modern deeds are being filmed, instead of being placed into books, as a matter of day-to-day operation by the recorder's office. I cannot testify as to whether all wills, probate records and marriages have been filmed from 1900 on.

There are many records that I do not believe have been microfilmed, including the following.

Auditor's Office: County Commissioners Records from 1817 on. The first book has been partly transcribed by Ruth Hoggatt and is available on www.myindianahome.net and there were two books, typed transcriptions of the first two books. These are indexed, but in a way that does not make them easy for family historians to use.

Auditor's Office: Tax Title Sales. These are the deeds that transfer land when an owner loses the property because of failure to pay taxes. If you lost track of your ancestor's land, it's possible it was for nonpayment of taxes and these are not included in the warranty deed books in the recorder's office.

Auditor's Office: Tax assessment records. There were few existing, 1827, 1828 1831 and 1833 for the whole county and 1829 for Madison Township alone. These have been placed on CD and are available through the Jefferson County Historical Society.

Auditor's Office: Land transfer records. Useful, but not critical. Organized by year and township.

Recorder's Office: Warranty deeds, as mentioned these have been microfilmed as have the deed indexes. They exist to the beginning of Jefferson County.

Recorder's Office: Sheriff's Deed Books. There are perhaps five of these and they cover loss of property via sheriff's sale. They are sometimes indexed in the warranty deed index books, but the deeds themselves are not in the regular books. Not microfilmed to my knowledge.

Recorder's Office: Entry books. These show original owners of tracts. The first set was abstracted by W.G. Ruesink and published by the Jefferson County Historical Society.

Recorder's Office: Mortgage records. Before about 1873, these include a lot of deed descriptions that simply reiterate what's in the deed book, but tie the sale to the loan. However, during this period mortgage books also record election of church and fraternal organization officers. They also include some freedom papers for blacks and some incorporation papers. They are hardly used and I don't they are microfilmed.

Recorder's Office: Miscellaneous Record Books. From about 1873 on, these include the church and fraternal organization elections, powers of attorney (often involve sale of a decedent's property and so valuable for family history research), lease and incorporations. Not microfilmed to my knowledge.

Recorder's Office: Apprenticeship book. There is only one of these to my knowledge. These can be very valuable for genealogist. I started transcribing it but didn't get far. It covers about the 1840s and 1850s--I only have referenced one of these in my family. These are not include in the Apprenticeship records abstracted in the 1900s by the John Paul Chapter DAR and have not been filmed

Recorder's Office: Articles of Incorporation. Record of incorporated companies from the second half of the 1800s. One book, not filmed.

Recorder's Office: Soldier's Discharge Record-Civil War soldiers. Ruth Hoggatt abstracted some of these, but not filmed to my knowledge.

Recorder's Office: Will Books. For whatever reason, perhaps four or five of these exist and are duplicates of what's in the circuit court clerk's office.

Recorder's Office:Gas and Oil leases. Not filmed

Circuit Court Clerk's office. Will, marriage return and marriage application books were in the office on the second floor. Other records were placed in the basement

Naomi Sexton published Book A of the wills in the Hoosier Journal of Ancestry. The DAR abstracted wills and two books were placed in the Madison library. I merged these two together and added probate records and estate settlements from deeds and suits. This is available at www.myindianahome.net.

Circuit Court Clerk's office. Guardianship Book. There was only one of these and I have not seen it in a long time. There was a report, I can't remember from who, that it was taken to Indianapolis, either the state library or archives. I know from records I used it included guardianships in the 1860s and 1870s.

Basement: Probate Order Books. Many of these were filmed. Wills from the 1830s and 1840s were filed in these not in books marked Will Books. This led many to believe wills from this period had not survived.

Basement: Complete Probate Order Books. A wealth of material if your ancestor's estate was recorded in these. Both these and the order books can include names of heirs. Not sure if the complete records were microfilmed.

Basement: Civil Order Books. The first Book, Volume A, is critical because at that time, the court not only handled probate and criminal and civil suits, but administered the county business. I am not sure it has been filmed. I believe Naomi Sexton transcribed at least part of this book and published it in the Hoosier Journal of Ancestry.

Basement: Complete Record Civil Order Book. Not filmed to my knowledge

Basement: Criminal Order Books. I forget how the spines are marked, but the criminal cases from the 1800s were in the basement and I don't think they were filmed.

Basement: Indexes to civil and probate books, after 1860. Early books each contained indexes, although since these were not bound to the main volume, some have disappeared.

Other abstracted records

Apprencticeship records. Abstracted by the John Paul DAR in the 1900s, they were transcribed by me and are available www.myindianahome.net. These appear to come from court books and do not include the volume in the recorder's office.

Naturalization records. Abstracted by the John Paul DAR in the 1900s, they were transcribed by me and are available www.myindianahome.net. These appear to come from court books

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Michael Bright Corners Madison's bank stock

The question is not whether Michael G. Bright, brother of powerful Senator Jesse G. Bright conspired to capture a lion’s share of stock at the branches of the Indiana State Bank. The question is whether financier James F.D. Lanier was in on the deal.

Bright did everything he could to control the sale of stock at

Technically, the

Bright acquired 1,200 of the 2,000 shares sold at

If in our modern view this procedure smelled rotten, there were many people who thought so then, which resulted in state senate’s appointing an investigating committee, which took testimony in January and February 1857, to see if there was corruption in the process legislature’s approval of the bill granting the bank charter.

During his testimony, Bright was unapologetic for his actions. “I took myself—sixty thousand dollars. I meant to take stock enough to control the branch at

The committee tried to determine if any legislators had been illegally influenced in their passage of the bill that established the process. David Branham, who represented the area in the general assembly, testified that when he and John R. Cravens (one of Lanier’s sons-in-law), who had voted for the bank bill as a member of the state senate, met with the commissioners who were running the sale, they were informed that the subcommissioners at Madison “must be acceptable to M. G. Bright.” Finally, it was agreed to choose three subcommissioners and then let Bright pick from those. But Bright chose none of those recommended. Branham said Bright offered him the chance to buy stock at the opening, but he did not accept the offer.

Perhaps the most stinging testimony given by Branham came in the following exchange. “Question. Were, or were not the persons appointed sub-commissioners for the

Bright was coy in denying there was undue influence on legislators prior to the passage of the bill as shown in the following testimony.

“Question. What do you know, if anything, about the friends of the bank being engaged in treating the members with oyster suppers, liquors, or otherwise, as a means of enlisting them in favor of the proposed bank charter?

Answer. I saw gentlemen, who, I know, were friendly disposed to the establishment of a bank, frequently eating oysters, and drinking liquors with members of the legislature; nor did I notice anything unusual in their doing so; nor did I regard it as a means of bribing them to vote for the bank.”

But he then said he knew nothing about any influence peddling.

Williamson Dunn, another one of Lanier’s sons-in-law, said he showed up at the office in

The committee clearly was trying to determine the nature of the agreement between Michael Bright and Lanier, who immediately acquired Bright’s

Cravens, who visited the Madison office that day, said he probably would have purchased some stock, but when he demanded to see the books, he was informed they were sealed and on the way to Indianapolis.

“There was dissatisfaction at

No one was able to point a finger directly Lanier and his company, Winslow & Lanier. But there was testimony the firm ended up with most of the stock of the

Saturday, February 28, 2009

First Family Non History

One of the most glaring examples was the DAR's decision to admit Johnston/Johnson Brown of Jefferson and Switzerland County, who, it was claimed died in 1869 at 109 and was supposedly squirrel shooting at age 100. Researchers Al and Margaret Spiry demolished this--suggesting the old man was simply a good story teller. Johnson's father signed to given him permission to marry in 1795 in Nelson County, Ky., meaning he wasn't 21 years old. Do the math.

There are some other great tales. The DAR has Ralph Griffin as having died in July 1838 and buried at Springdale Cemetery. However, the Jefferson County Probate records show he died on Sept. 13, 1838 at the hosue of John Rogers (his grandson-in-law and executor) in Switzerland County. Since Rogers lived near Pleasant, and since Rogers and Ralph's wife Catherine and son David Griffin are buried at Brushy Fork Baptist Church, it's more likely his unmarked grave is there. By the way, the newspaper article about the burial said simply that a Mr. Griffin was buried in July 1838 (and Springdale was established in 1839.)

Then there was George Buchanan, whose family established Buchanan's Station, the blockhouse on the Jefferson County-Ripley County line, in 1813 according to the DAR, in 1812, according to a contemporary account.

George lived 1721-1818 according to the DAR's records; lived to be more than 100, according a newspaper article of the reminiscences of his grandson George W. in 1910, or died in 1815, according to a stone that now stands in the Buchanan family cemetery opposite the replica of the blockhouse. (It was probably moved there about 1985 from the McLaughlin Cemetery)

Many individuals have been admitted to the DAR and SAR based on the Pennsylvania Archives that show George Buchanan served from 1777 through 1781 in the Fourth Pennsylvania Continental line. The problem is, the record does not say which George Buchanan, and there are plenty to choose from in that place and time.

Now, U.S. records show that in 1786 Ezekiel and Elizabeth Buchanan, no relationship given, were paid for services of George Buchanan in the Fourth in Pennsylvania. They were paid with interest accruing from Jan. 1, 1781, which suggests the service ended on that date. The only conceivable reason someone other than the solider would be paid is that the solider, George Buchanan, had died by 1786.

Then there is Gerardus Ryker, who the DAR was Gerardus was an ensign in Col. Theunis Day's Bergen Co. Regiment, New Jersey Militia and was also an ensign in the Battalion of Major Mauritious Goetschius, New Jersey State Troops, serving extending from 1776 to 1781.

Ryker, however, moved to modern West Virginia in 1778, then to Kentucky in 1779 and was killed by Indians in that state in 1781. Based on my suggestion this didn't make since, Lynn Rogers of Dayton, Ohio, pursued this conflict and believes the Gerardus in New Jersey was a relative of the same name.

Our final problem is Samuel Welch. The DAR put a stone at his family plot on Scott's Ridge, Shelby Township, commemorating his Revolutionary service in Springer's Legion. Unfortuantely, Springer's unit served in the Indian Wars after the Revolution was over. In fact, the DAR started rejecting applicants because Samuel's initial pension application was rejected because of this fact. However, when he resubmitted his claim, it was approved. Either Samuel served as a teenager, or he was a complete liar--take your pick

Then, there's the question of his wife's maiden name. The book, "Welch and Allied Families," which was printed in 1932, carried a transcribed letter from Knox Jamison, that had been written in 1924. Jamison wrote that he checked Samuel's Bible (the one I own and that was passed down along with his farm in my family), and gave Samuel's marriage to Jane Cunningham in 1797. The Welch Book author created a nice family tree for Jane that many descendants have elaborated on, listing her parents as a John Cunningam and Ann Sinclair, who lived in Massachusetts.

There are two probems with this. The first is that some Cunningham researchers show this couple's daughter Jane, who married a Samuel Welch, died in Massachusetts. The second problem is that's not what the Bible says, and the author who transcribed Jamison's letter simply got it wrong.

The Bible shows her name as Jane Cumming (it actually looks more like Cunning, but I think that's an issue of handwriting.) There's another family Bible, one that Samuel reportedly carried with him as a soldier, that shows her name as Cummins or Cummings (the last letters are blurry.)

And this are merely lines I have investigated well. Imagine the possibilities!