This chronology is designed to paint a picture of the exploration of Jefferson and Switzerland County up to the point permanent settlement began and the counties were created.

1729/39. Chaussegros de Lery draws a map of the Midwest showing the Kentucky River and marks that elephant bones were discovered at what is now called Big Bone Lick (opposite Posey Twp.) The map'

s date is debated by historical researchers. 1753 Christopher Gist's party stops at the Salt Creek coming from Big Bone Lick. He may have crossed the Little Kentucky River near its mouth, but his knowledge of geography was incorrect so it is not possible to determine his exact route.

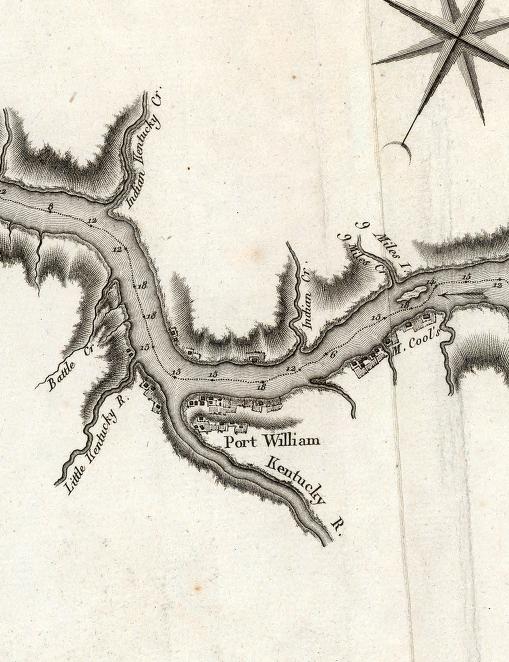

1753. The so-called Trader's Map shows a stream in the correct position to be the Indian-Kentuck Creek in relationship to lines of attitude and longitude although details or the Ohio River are rough.

1766, March 19. John Jennings passes the mouth of the Kentucky River with an expedition at half past nine in the morning. He notes Indian cabin on the point of a creek on the Indiana side at 4 p.m.

1770. Daniel Boone follows the south shore of the Ohio from the Licking River to Louisville.

1774, May 23 Thomas Hanson surveys 2,000 acres in the Ohio River bottom just upstream from Milton, Ky.

1778. Letters from Henry Hamilton, the British governor at Detroit, on April 25 and September 25, mention a settlers’ fort at the mouth of the Kentucky River.

1778 Thomas Hutchins maps the Ohio showing unnamed streams in the current latitude and longitude, including the Indian-Kentuck and Indian Creeks.

1780. The Low-Dutch company, including the Rykers who will be the first known settlers of Jefferson County, float down the Ohio to Louisville.

1780. George Rogers Clark scouts the mouth of the Kentucky River, deciding not to build a fort there.

1780. "Indian" George Ash and several brothers captured in Nelson County, Ky., by Shawnees.

1782. Spring. Indians carrying a party of 30 whites, including the Polk family, across the Ohio at the mouth of the Kentucky River. They are the first known Europeans to visit Switzerland County.

1782. August. John Ryker is sent up the Ohio to spy and reports he went "in various direction as occasions required."

1784. John Filson draws a map of Kentucky that shows the Indian-Kentucky Creek in the correct position and calls it the Indian-Kentucky. The map is published in 1793.

1785, March. Indians kill members of a family who had recently settled at the mouth of the Kentucky River.

1786 May 3. Journal of the Continental Congress mentions ordinance passed May 20, 1785. which described land "lying upon the river Ohio, between the little Miami and Indian Kentucky."

1788, July 9. The Territory Northwest of the Ohio begins keeping records.

1789. (July) Whites kill several Shawnees women and children opposite the mouth of the Kentucky River.

1789. A white vigilante group attacks Indians at a point twenty-six miles down river from

the Great Miami. The distance places the attack in Posey Township, Switzerland County.

1789. Milton, Ky., founded opposite Madison.

1790, February. John McMullen captured by Indians on the Indiana side in retaliation for the 1789 white attack in the same place opposite the Kentucky River.

1790. The Gershom and John Lee families, who would settle in eastern Jefferson County, make their home at the mouth of the Kentucky River.

1790, June 20. Knox County created. It includes all of modern Indiana.

1791, May 19-May 23. General Charles Scott and 750 mounted volunteers cross the Ohio River at the mouth of the Kentucky River or further five miles down, crossing Jefferson County on their way to the Wabash

1793. Matthew and Peter Smock are captured by Indiana in Shelby County, Ky. The captors camp for three days at the future site of the Jefferson County courthouse.

1794, October 6. The territorial government reports several men are making illegal surveys on government and Indian lands west of the Great Miami River.

1795. Heathcoat Pickett leaves the Indians with whom he lived and settles in Switzerland County.

1795, November 28. The Kentucky Legislature grants a license for a ferry from the newly approved town of Preston across the Ohio River. [Modern Prestonville, near Carrollton, at the mouth of the Kentucky River.]

1795. Matthew and Peter Smock are ransomed during the negotiations for the Treaty of Greenville, which establishes the treaty line from Fort Wayne to the mouth of the Kentucky River.

1795, August 3. Treaty of Greenville signed. The U.S. buys the area that will become Dearborn, Ohio, and most of Switzerland Counties

1796. Former French General Victor Collot surveys American rivers on a secret mission. He mentions the Indian-Kentucky Creek by name and Battle Creek (modern Locust Creek in Carroll County). He left Pittsburgh on March 21

1797. George Ash settles in the Lamb area. Ash swears on January 29, 1802 that he has lived in Indiana on the land given him by the Indians for the last four years.

1797, June. Israel Ludlow begins surveying the Greenville Treaty line at its northern end.

1797/1798. Settlers from Nelson County, Ky., begin settling in Switzerland County.

1798, October 15. Jean Jacques Dufour begins buying land for his first vineyard on the Kentucky River.

1798, June 22. The area east of the Greenville Treaty line, including Switzerland County, becomes part of Hamilton County, Northwest Territory. Jefferson remains in Knox County.

1799, August 6. Jonathan McCarty appointed Justice of the Peace for Hamilton County, which then included Switzerland County.

1798, January 8. The territorial government reports about two hundred families have settled just west of the Great Miami River in what was then Knox County.

1799, July 23. Captain E. Kibbey finished 70 miles of a road from Vincennes to Cincinnati. The road will cross Jefferson and Switzerland Counties before 1805. Undocumented reports say it crossed Switzerland in 1801 or 1802.

1800, July 4. Indiana territorial government begins operating.

1800, December 3. Jonathan McCarty's daughter Lydia married Gershom Lee in Gallatin County, Ky.

1800, October 12. Polly Netherland married David Owen in Hamilton County, Northwest Territory. The transcription show the justice as Jonathan County, probably McCarty. This is the earliest known marriage recorded for Switzerland County. He also officiated at the marriage of his cousin Paul Froman to Kesiah Pickett in Hamilton County on November 13. All were known Switzerland County residents.

1801, February 3. Clark County created. It includes Jefferson County and the part of Switzerland County east of the treaty line. 1801, July 15. Gen. William Henry Harrison writes that Indians complain that whites cross the river in the fall on hunting expeditions from the mouth of the Kentucky to the Mississippi River.

1802, January 29. George Ash petitions Congress for rights to land granted him by the Shawnees.

1802, February 5. Shawnee Chief Black Hoof tells Thomas Jefferson the Indians want to give Ash a tract one-mile deep by four miles long, measuring from the mouth of the Indian-Kentuck Creek and down river.

1802, July 5. Heathcoat Pickett, who stayed in Switzerland County, and William and John Hall, who would move to Madison by 1807, are commissioned in the Indiana militia.

1802, May 1. Congress grants Dufour's vineyard company 2,500 acres in Switzerland County.

1802, October 5. As resident of Indiana, Captain William Hall and Gershom Lee sign a petition in support of Ash's land claim.

1803, January 24. Switzerland County east of the treaty line, Ohio, and Dearborn Counties become part of Clark County.

1803, March 7. Switzerland and Ohio County areas become part of newly created Dearborn County.

1804, December 30. Captain William Hall, Jonathan McCarty, and Gershom Lee sign another petition in support of Ash's land claims.

1810, November 23. Jefferson County created, extended east to Log Lick Creek.

1814, September 7. Switzerland County created.