[Editor's Note: While Jean Jacques Dufour lived in Switzerland County, not Jefferson, his activities are of interest to many.]

He got the ear of a president, Thomas Jefferson, who could read and answer the letters that Dufour had written in French. He persuaded the U.S. Congress to allow him to buy land at terms not available to others. And he got press coverage that gave his operations the appearance of being far more successful than they really were.

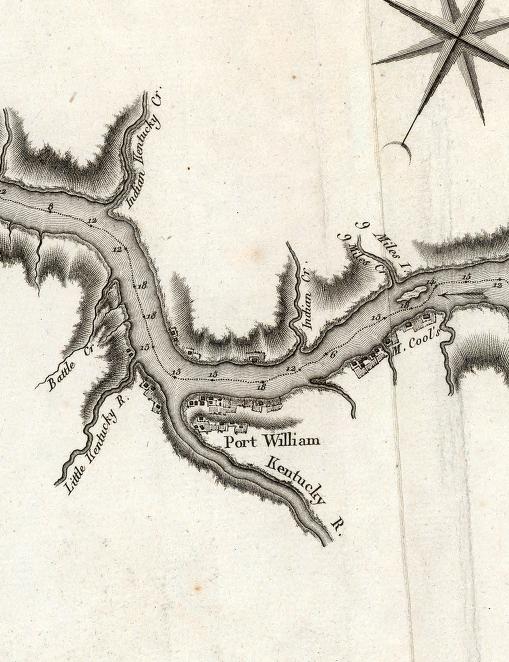

Jean Jacques moved into the public eye after purchasing land in

Dufour started on his American venture on March 20, 1796 and spent the next few years buying and selling goods, such up and down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and throughout Kentucky, in order to raise money for his dream of an American vineyard.

The difficulties in growing grapes, the lack of interest of the proprietors, is mentioned by this account as a factor in the failure along with "the division of M. Dufour’s family, a part of which was on the point of quitting it to settle on the banks of the Ohio." That, of course, was the origin of the Swiss settlement in Indiana.

To start the Indiana effort, Dufour wrote Thomas Jefferson [in French and English] a woeful tale of five families, all experienced vine keepers, who left Switzerland because of heavy losses of property stemming from war and revolution there. Meanwhile, he had described the First Vineyard in Kentucky as having "the most flattering prospect of complete success."

What Dufour wanted from Jefferson was a simple request of getting Congress to grant him the ability to purchase 2,500 acres in what would become Switzerland County at two dollars per acres, to be paid in 1812, ten years later. This compares to everybody else who, before 1820, got three years to pay. Not only would the vineyard be a valuable form of agricultural, but Dufour assured the president "that the land which your petitioner wishers to purchase can only be useful to cultivation of the vine …" that except for a small piece on the river "… being either abrupt hills or deep valleys, and such as in all probability would not sell before the period contemplated for the payment to be made by your petitioner."

That last statement would probably have come as a surprise to people like the Picketts, who were squatting on the land, and who were displaced when Dufour and his associates claimed it.

Congress went along with this deal. Then, Dufour got stuck in Europe during the War of 1812, with payment due in 1814. So he petitioned Congress for another five years to pay. He got that. But when 1818 rolled around and he was asked for 12 months to pay because the government was requiring payment in coins, not notes, part of Congress rebelled. A committee of the House of Representatives split 7 to 7 on the bill and in December 1818, the House rejected the bill by a vote of 65 to 66 on a third reading.

Somebody must have twisted some arms because the bill came up again on December 23, 1818. The official record noted, "The debate was more animated than at the first glance one would have expected such a question to produce." It was spirited enough that it lasted past the usual time for adjournment.

Dufour finally got his way when it passed by a vote of 73 for and 67 against with the record noting that, "The bill was opposed on the general grounds of the inexpediency of making a discrimination between these claimants and other petitioners."

While the congressional records show no final vote, Dufour paid since he got title to the land. Of course, the final kicker to all this is that he wasn't required to use it for growing grapes, so to a certain extent, the Dufours were given 15 or so years to pay for an investment in real estate that they then sold to other settlers.

No comments:

Post a Comment