It’s a story that’s difficult to document. But the indications are that the native Americans encountered by settlers were a mixture of tribes, escaped slaves along with a mixture of European blood from white captives and willing marriages.

Some captives, like Heathcoat Pickett and George Ash, lived among the Indians for years. Little has been written about Pickett, before he settled in what became

Whether he intermarried with his captors or not, Pickett lived long enough with the tribes to have his ears multilated for adornment . The same is true of the better-known Ash who had the septum of his nose perforated while his left ear was also perforated for the placement of jewlry. Ash also had an Indian wife known as she bear. What is not known is whether the couple had children before Ash returned to white settlements and remarried.

A strong hint of interbreeding was given by James Jackson, who settled in the Kent area

“Old Wea was a black, nasty, mottled color, not a white man, nor a nigger. Old White Eyes was a yeller Indian and so was his son.”

While

Another account printed in the Courier was from Hiram Prather, who lived in

There was a lot of opportunity for commingling.

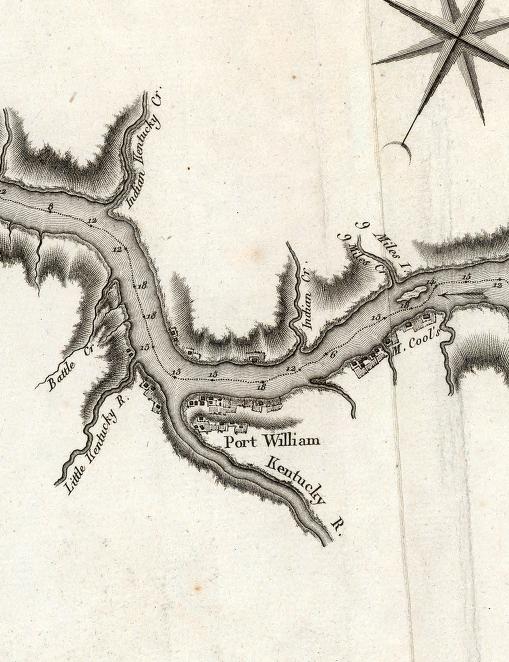

Two Indians with European names, Wilson and John Guinn, were reported to be living in the house of Gershom Lee in 1812. (Lee lived just downstream from Manville in 1816 and was probably there in 1812) Sometime before the Pigeon Roost Massacre, the two were hunting at the headwaters of Indian-Kentuck Creek when they were shot and killed. Two settlers, William Hall and a Lockridge, heard the gunfire and found them dead on the ground. (These is the account that probably gave rise to the story of the killing of White Eyes. Evidence suggests that White Eyes was not murdered.) This account was given in a letter dated Sept. 9, 1812, which was written by adjutant general Percival Butler.

It is known how long the Indians lived in Lee’s house or why they were there, although stories about White Eyes suggest the natives frequently visited settlers homes for meals.

Some mixing took place before settlers arrived in

There were white-Indian marriages in the

George Miller, who wrote a column for the Madison Courier for decades in the late 1900s, often described how his ancestor Jacob Miller was buried next to the wall of the Manville cemetery because Jacob had married an Indian. Not far upstream in Madison Township, Samuel Brown, who was born about 1799 in Pennsylvania, is supposed to have married a woman named Half Moon, although the presume wife shown in the household in the 1850 census was Matilda, aged 45.

The censuses aren’t any help. The 1840 census asks only for a number of free blacks in Hoosier households while the 1850 and 1860 censuses asked only if residents were white, black or mulatto. And it’s easy to think those who were Indian, didn’t spread that information easily or often.