Sometime during the first half of 1861, the steamboat, the “Masonic Gem,” began sailing a regular route between Madison and Louisville under a permit issued by the military authorities, who were regulating Ohio River traffic. But the permit was fraudulent, while the ship was “heavily laden with provisions destined for the Confederacy,” according to the Cincinnati Daily Gazette of June 17, 1861. It was a brief episode, since its operations were made public. But illegal traffic from Madison was a problem throughout the War.

Part of this could have been war profiteering, in which participants take only the side of the most money.

For example, soldiers blew the whistle on one scam. According to a soldier from Vevay, in an account printed in the Vevay Reveille of Aug. 29, 1861, five cavalry companies left Madison on five boats on August 26. There were supposed to be six, but the writer claimed that and Col. Wharton and Bob Lodge of Madison tried to cut corners.

The soldier’s letter alleged the two, responsible for feeding and transportation, wanted to cram the men into four vessels, rush them to Pittsburgh without supplies or cooking facilities, charge the government for six watercraft, and pocket the profits. However, junior officers blew the whistle and supplies and five boats were provided.

While there’s no need to recount in detail here that Madison-resident, Senator Jesse Bright, owned slaves in Kentucky, the city had its share of Southern sympathies, if not actual sympathizers. The well-known writer William Woollen termed Madison a “quasi-southern city,” which is emphasized by the plantation mansion appearance of J.F.D. Lanier’s home (even though he was a stout Unionist.)

The commercial connection was strong. According to a 1903 account detailing the history of Methodist Churches in Madison, “Residents choose sides, in many cases, according to their financial interests. Flour, pork, lard, and hay had found ready sale down South and very naturally pecuniary interests were paramount to patriotism, and most of the citizens connected with the flat-boat or steamboat interests were Southern sympathizers.”

How many actually aided the South is not known. But the Louisville Democrat, as quoted in the Reveille of June 30, 1861, outlined a plan under which hundreds of barrels of bacon and pork were to be diverted to the south. These barrels were shipped under the name of Madison’s Powell, McEwen & Co., whose name was replaced with that of Guthrie, White & Co.

About the same time, Capt. David, a well-known Madison steamboat man, refused to unload a delivery of pork in Louisville and took it back to Madison after he could not get guarantees that the barrels would stay in Louisville.

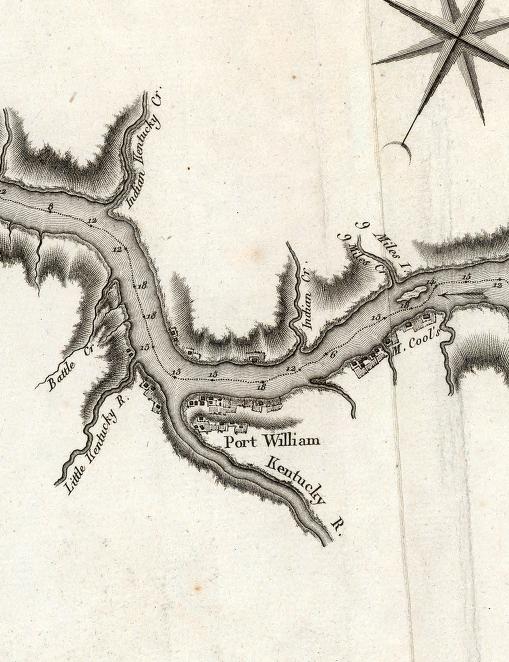

Goods weren’t just going downriver. Various newspaper articles reported a brisk trade from Southern Indiana to the south via the Kentucky River.

The Sept. 12, 1861 issue of the Vevay Reveille noted the Madison Courier had reported “It is also alleged that illegitimate shipments from Madison are daily being made.” The Madison Courier of Aug. 29, 1861 noted the North had stationed 200 to 300 soldiers Cedar Lock on the Kentucky River to make sure no boats passed without being searched.

No comments:

Post a Comment