When the Disciples of Christ burst upon the scene in the Midwest in the early 1800s, churches divide and old friends turned against each other. In fact, this seems hardly an overstatement giving some of the evidence that emerges about this doctrinal battle.

The friction was shown in the attitudes of the Coffee Creek Baptist church in Jennings County, not far from the Jefferson County border. On the First day of Saturday December 1835, the church minutes show: “On motion is it decided by this church that John B. New and all that hold with him shall not be permitted to preach in our meetinghouse.” And the next action it took was to approve purchase of a lock for the meetinghouse.

New had been a Baptist minister. But he was one of the many who turned to the Christians, who were variously known as Campbellites, after their founder Alexander Campbell, Christian Baptist and Reformers, related to the Reformed Church, which is how the denomination thought of itself as reforming a religion that had strayed from the rules of the Bible.

New arrived in Madison in 1815 and over the next two to three years, he was clerk for the Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church on the Madison Hilltop, the first church (counting it as a successor of the Crooked Creek Baptist Church), founded in Jefferson County.

After attending some of the meetings in Kentucky, he returned to Mt. Pleasant filled with the message and decided to become a minister in 1818. That same year he married and was also on a committee to rewrite Mt. Pleasant’s rules. In the words of an author committed to the truth of the Christian message, New convinced the committee that the only rules it needed were those of the New Testament. The biographical sketch in the book Biographical Sketches of the Pioneer Preaches of Indiana also makes it clear that the Christians saw themselves as in revolt against the Calvinist doctrine of predestination.

The lock at Coffee Creek was just one evidence of conflict. Among the members of the Church of Christ, organized by New and Carey Smith in Madison in 1832, was another elder, Jesse Mavity, who had taught school in the basement of the Masonic Hall along with his brother Henry. “Prior to the organization of the church, who had preached with great acceptance for the several denominations of the city, all of whom were liberal patrons of his school,” But because of Mavity affiliated with the Christians, when he changed his school to a high school, the subscribers withdrew. This account makes it sounds as if the Mavitys were set up for failure by those who urged the change in schools; another that the school was simply abandoned by opponents the new denomination.

Churches changed affiliations. The first Baptist Church in Indiana, the Silver Creek Baptist Church in Clark County, joined the Christians. Two New Light Churches (a dissident form of Presbyterianism), a church named Liberty near Kent and another another Liberty Church at Mud Lick (later called Bellview) became Christian bodies in the 1830s.

But one of the bitterest fights took place in Milton Township, where the newly founded Milton Church found itself subject to the divisive forces. It may not have been more bitter than elsewhere; but three accounts show that it must have been a heated discussion.

All of the accounts have some errors and they gloss over some of the pertinent points, partly because two were written from the viewpoint of the Christians and the other because it was a local history, whose main purpose wasn’t defining religious movements.

The Milton Baptist Church was founded in 1829 in Milton Township about two miles east of modern Manville. It was the first church that organized in and met in Milton Township.

It must have been subject to tension from the beginning for a History of Milton Township written sometime before 1908, probably by William Ryker, then president of the Jefferson County Historical Society, refers to the Manville Christian as growing out of a Manville Baptist Church. No such body every existed—it clearly grew out of Milton.

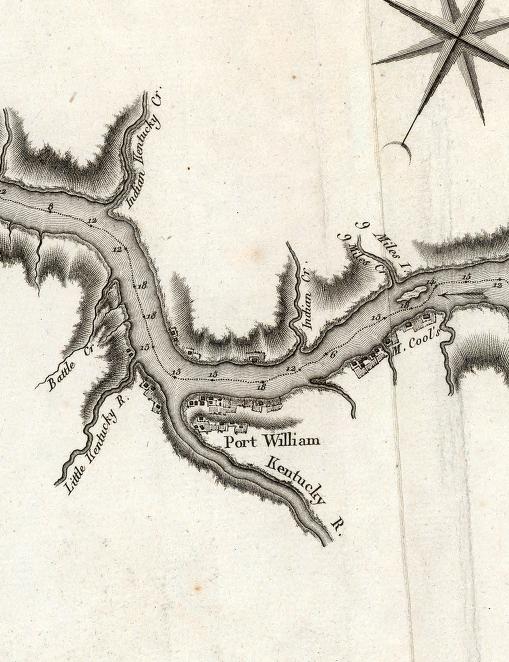

This account says the church had two ministers, Benjamin Levitt and Joseph Hankins, who were divided on practice, one for open communion, one for closed communion. Then Jacob Short, who had been one of the founders of the Indian-Kentuck Baptist Church, included Beverly Vawter to speak. Son of Baptist minister Philemon Vawter and nephew of Baptist minister Jesse Vawter, Beverly had gone over to the reformers and was a major force in Jefferson and Switzerland County. Hankins, who was the minister at Milton Baptist Church in the early 1830s gets no more mention in his role in the events. But Levitt was an important player.

A biographical sketch of Beverly Vawter, in the same volume that profiled New, said that in the summer of 1830 “he was invited to attend the monthly meeting of a Separate Baptist church near the forks of Indian Kentucky. Their preacher and elder was a man by the name of Levitt, who was bitterly opposed to what he was pleased to denominate Campbellism.”

After Vawter preached and four members confessed and were to be baptized, Levitt was requested to attend their immersion and refused with "No, sir, they are your converts—I will have nothing to do with them." At the next church meeting, it was clear Vawter had won. (The formality of the quotes attributed to Levitt sound like they were constructed in later years, fairly typical for writings of the era.)

The story concludes with “This was the origin of the Church of Christ, now* known as Milton

Church, which still yields the peaceable fruits of righteousness under the pastoral care of Charles Lanham.” This time, the error in church names goes the other way. Because Lanham was known to be a minister at Manville Christian Church, and given the location at the forks of the Indian-Kentuck, the new body was clearly Manville.

Important points are lost here. Levitt, a native of Rhode Island, represented a more liberal Baptist view in which the ministers were sometimes affiliated with the Free Will Baptists, sometimes with the Separate Baptists. The Free Wills formed several congregations in Ripley and Switzerland County, but none in Jefferson County (unless the Milton Church was temporarily a free will). The Separate Baptists had only the church at Center Grove in Shelby Township, which became the regular Hicks Baptist Church in 1894, while there were more in Switzerland and Ripley Counties. Both bodies were non-Calvinist and most congregations were decidedly anti-slavery. There may have been a regional split—a more educated Northeasterner against the home grown ministers. It’s likely there was a whole mix of issues.

In any event, important members of the Milton Church show up in records of the Manville church from its founding. John Lanham and William Yates, who were messengers from the Milton Church to the Coffee Creek Baptist Association in 1829, were members No 2. And No. 4 respectively on the Manville membership list and Jacob Short was No. 21. There are no dates on this list before member No. 36, but it’s possible these were all charter members. And they brought their families within them. The final word on the Hankins role was that they stayed with Milton. Joseph Hankins died in 1836 and the church disbanded, but it reformed with his children playing a major role.

The third account, again from the Christian side, was a letter written on April 7, 1834 and printed in the Christian Evangelist. Its language is pious, bordering on haughtiness.

Not naming the church, but noting its location on the Indian-Kentuck Creek, the writer reported, “We esteem the word of God as living and effective and since we got rid of the Babylonians, thirteen of fourteen have been added to our number. Seven of the old folks remain obdurate, two of them were elders and one a Rabbi.”

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

A Mississippi Fight Over Free Jefferson County Blacks

At the first glance, it's easy to miss that there was anything unusual about James Brown, a 64-year old man who was born in South Carolina and whose household was shown in Lancaster Township, Jefferson County, in the 1850 census as enumerated on October 25 that year. But a closer look hints that there was something very different.

The census shows Brown, indicated as white since no race was listed, with five other individuals in the household, all mulattoes. They were Harriet Brown, age 34, Francis Brown, age 18, Louisa Brown, age 11, Jerome B. Brown, age 7, and Theresa V. Brown, age 2, all born in Mississippi. The 1850 census did not record relationships so it could not show that Harriet was Brown's slave and mother of the four younger Browns who were also James' children, and under the laws of Mississippi were his slaves when they were born.

These details emerge via a court case, Shaw vs. Brown, decided by the Mississippi High Court of Errors and Appeals in April 1858, which shows that this family became the subject of a court fight pitting James' brother John and some nieces and nephews against their mulatto cousins as the former tried to claim the children who remained slaves when James died. For reasons not stated, the case revolved around Francis and Jerome only, with the two daughters not mentioned—perhaps they lacked the market value of healthy young male slaves, or they were not listed by name in the will.

The court's decision spanned about 34,000 words, but taking out the legal arguments, the facts were that James took the children to Indiana to receive an education and that he also intended to set them free, which he did via a will dated Oct. 9, 1853, and then died in 1856. Their status was also the subject of freedom papers filed for Francis and Jerome in Jefferson County and recorded in a mortgage book, unfortunately part of the records awaiting possible restoration following the 2009 courthouse fire.

The family's stay in Jefferson County was brief. Brown moved to Greene County, Indiana, in 1855, and died there. Harriett and the three youngest children were shown in Fairplay in Greene County, in the 1860 census. Francis, apparently married, headed his own household there. However, the reasons for their presence in Lancaster was very important.

Although it's not spelled out in the court papers concerning where Brown intended to obtain the education for his children, it seems obvious he came to Lancaster Township so they could attend the Eleutherian College. I do not know if college recorded their enrollment, but the 1850 census shows Brown and his family two households before John Craven, that institution's founder.

A variety of legal arguments went into the effort by Brown's relatives to re-enslave his children. They argued he couldn't legally take them out of state to free them and also cited some visits in which the older children visited Mississippi as a return to residency in the state. And the plaintiffs cited the 1850 constitution of Indiana, which barred the entry of free blacks into Indiana after 1852, another issue in their claim that the will should have been voided. They wanted Brown declared intestate, in which case the children could be sold and proceeds distributed to the other heirs.

They disputed facts that James claimed paternity of the children, some witnesses claiming he never said he intended to free them, while the plaintiff claimed he took Francis and Jerome to Cincinnati in 1849, intending to free them, and executing an emancipation deed, but then returning with them to Amite County, Miss. to live and that they spoke of that state as their legal residence. The plaintiff also claimed James Brown said he was going to sell the children, while at the same time alleging he fraudulently took them North to free them with the intention of returning to the South.

Richard Shaw, one of the executors, said Brown didn't make it to Cincinnati because of low water in 1849, but did reach that city and freed them and their mother on May 11, 1850 and that they settled in Indiana and lived in the state from that time on.

The list of witnesses included James' Brown, John Brown, and John's son, William, and E.A. Haygood, a son of a deceased sister of James, along with Joseph Richardson, one of James' Brown's plantation overseers, whose testimony was designed to show James didn't intend to free his children and that they had maintained their Mississippi residence. Statements were made on both sides by what appear to have friends and neighbors, including some that said the children called Brown "father" and he treated them as such.

Strong testimony in favor of the Browns' having become Hoosiers came from nine Jefferson County residents, including James Nelson, who was active in the Underground Railroad. All lived in the Lancaster area. While another executor, Lemuel Hanks had resigned his position, Richard Shaw took an active and sympathetic role and had warned Francis Brown not to return to Mississippi. Unfortunately, the group didn’t spell out the educational plans. However, Nelson had served as an officer of the Eleutherian College.

The court held it didn't matter in Mississippi what the Indiana law said--the Browns had been allowed to live there and it was Indiana’s business if it didn’t enforce its own laws. It also found there was nothing illegal in Brown's taking the children to Indiana for an education, which, as slaves, they could not get in Mississippi.

The Mississippi court, however, appears to have made a major legal blunder. It said that the Brown children's residence in the Hoosier state because during that time, "the relation of master and slave was of necessity dissolved." However, my reading of the Dred Scott decision, issued in 1857 by the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that moving to a free state did not remove slaves from their position, which made the decision highly unpopular in the north. While the court's statement was in error, the fact that Brown executed deeds to free his children, made it a moot point. (As a non-lawyer, I believe Dred Scott meant Brown had to utilize a legal document to free the children, not simply move them north).

Since a slaveowner could not utilize a will to devise property to a slave, the court's pivotal question was whether Francis and Jerome were free blacks when the will was made, largely proved by the testimony of an Ohio notary who witnessed the emancipation deeds. Whatever the judge's personal opinions, they rejected a lower court ruling which they said was partly based on prejudice against Negroes, not only the law.

After all the arguments, the court ruled the Browns were free, reversing the lower court.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Six Feet Under: A Brief Review of Cemetery Histories

Cemeteries have histories. And as a meeting place of East, Mid-Atlantic and South, Jefferson County was a mixed of the different kinds of cemeteries, which developed in different ways.

The rural South tended heavily to family cemeteries in the early years, as did much of Jefferson County with its strong southern contingent. The more urbanized East had more town cemeteries, and perhaps because early Madison's leadership included a number of New Yorkers, the town had a cemetery at the site of John Paul Park, which was removed to Fairmount late in the 1800s. Meanwhile, Madison founded Springdale Cemetery, a municipal cemetery, the only one of its kind if Jefferson County, but by far the largest.

Church cemeteries were often connected to the family cemeteries, particularly in the Indian-Kentuck basin that drains must the eastern section where several family burying grounds became the official church graveyards. Why is not known, but perhaps there were simply fewer good locations because of the hilly landscape.

The Milton Baptist Church, which existed from 1829 through 1836, and then from 1840 through 1883, was deeded its church cemetery in 1871 by Aaron and Sarah Hankins and it had previously been the Hankins family cemetery.

The origins of other church cemeteries are not so clear. But those with burials before the churches' founding include the cemetery of the former St. Anthony's Catholic Church at China, where the earliest burial, that of James Hamilton in 1847, preceded the church's founding. The Hamiltons were likely not Catholic and local families had an oral traditional about non-Catholic burials there.

Similarly, although the former Olive Branch Methodist Church in Madison Township was founded in its first burial was for Susan Hamilton, wife of James (the same James?), who died in 1820.

At Canaan, the burial of a Littlejohn came before the organization of the defunct Canaan Methodist church in 1834. The same is true for the Brooksburg Cemetery where are marked graves for 15 Bondurants who died before the founding of the Methodist Church there in 1891. Likewise, at Manville, where the church's founding preceded the establishment of the cemetery, several members of the Manville family were buried whose names appear nowhere on the church membership record.

The cemetery of Ryker's Ridge Baptist Church presents a more confusing case. There were at least three burials there (one Hillis, one Van Cleave, one Ryker), before a non-denominational church reportedly was founded in 1818, although there is no proof the cemetery was associated with that body. And while the Baptist Church was founded in 1840, there are other marked graves, 13 Hillis stones and 4 Ryker stones (not including the unmarked grave of John Ryker), which have dates for those who died before 1840. Complicating this is the fact there was a Presbyterian Church at Ryker's Ridge, possibly from the early 1820s through the mid 1830s. Both Ryker and Hillis families were largely Presbyterian at this point.

In the western part of the county what is now called the Wiggam Cemetery in Graham Township was originally known as Deputy's graveyard. That was the name it had when John and Elizabeth Wiggam deeded it to the trustees of the United Methodist Church on May 4, 1881. It's the only such transfer of a private graveyard to a church I have yet found in the western part of the county.

Community cemeteries also started early in the county's history. The cemetery now associated with the Hebron Baptist Church was founded as a private burying ground with the earliest burial in 1814 or 1815. It had its own trustees as late as 1830 and the land was later deed to the church, which was founded in 1828.

Also in Monroe Township was the Craig Cemetery, whose first known burial was in 1819. Then on Feb. 26, 1831, William, and his wife Mary Richie, and William Wallace, and his wife Sarah, deed land to the trustees of the burying ground. It was moved to Madison Township with the formation the former Jefferson Proving Ground in 1941.

The only community cemetery in Milton Township, the Joyce Cemetery, has obscure origins. Its first burials are from two families, the McKays and Brooks, and it may have taken shape because the nearby Home Methodist Church (ca. 1830-ca. 1970), had a location that regularly flooded. Certainly, the Brooks were largely Methodist. The earliest known burial was of Ann, wife of Humphrey Brooks, who died in 1832 and the second was for Nancy Brooks Neal, their daughter. The cemetery reportedly took its name from Pliny Joyce who had owned the land.

There are several cemeteries in the county that belong to vanished churches, and whose prior associations are not widely recognized. The Carmel and Old Bethel Cemeteries in Hanover Township are fairly well known as having been burying grounds for two extinct Presbyterian Churches.

Lesser known affiliations include the Valley Cemetery in Graham Township had been the graveyard for the Valley Methodist Church, but was transferred to a cemetery association. The McKay-Stites Cemetery in Smyrna Township may have been associated with the Upper Big Creek Presbyterian Church, later called the Mt. Pleasant Presbyterian Church and which faded into history after it moved to Dupont.

Interestingly, one trend in cemetery formation passed by Jefferson County, and that was the founding of burial grounds by fraternal groups. In Kentuckiana area, this meant primarily the Masons and the International Order of Odd Fellows.

Vevay's Cemetery was founded by the IOOF as were the Bedford and Carrollton, Ky., burying grounds and cemeteries in New Liberty and Owenton in Owen County. Ghent in Carroll County and Dallasburg and Monterey, Ky., in Owen County, have Masonic cemeteries.

There are probably two factors here. The fraternal cemeteries functioned essentially as town cemeteries and that role was already occupied by Springdale in Madison. Also, the other areas lacked Madison's Catholic population, which utilized St. Joseph's and St. Patrick's.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)