When the Disciples of Christ burst upon the scene in the Midwest in the early 1800s, churches divide and old friends turned against each other. In fact, this seems hardly an overstatement giving some of the evidence that emerges about this doctrinal battle.

The friction was shown in the attitudes of the Coffee Creek Baptist church in Jennings County, not far from the Jefferson County border. On the First day of Saturday December 1835, the church minutes show: “On motion is it decided by this church that John B. New and all that hold with him shall not be permitted to preach in our meetinghouse.” And the next action it took was to approve purchase of a lock for the meetinghouse.

New had been a Baptist minister. But he was one of the many who turned to the Christians, who were variously known as Campbellites, after their founder Alexander Campbell, Christian Baptist and Reformers, related to the Reformed Church, which is how the denomination thought of itself as reforming a religion that had strayed from the rules of the Bible.

New arrived in Madison in 1815 and over the next two to three years, he was clerk for the Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church on the Madison Hilltop, the first church (counting it as a successor of the Crooked Creek Baptist Church), founded in Jefferson County.

After attending some of the meetings in Kentucky, he returned to Mt. Pleasant filled with the message and decided to become a minister in 1818. That same year he married and was also on a committee to rewrite Mt. Pleasant’s rules. In the words of an author committed to the truth of the Christian message, New convinced the committee that the only rules it needed were those of the New Testament. The biographical sketch in the book Biographical Sketches of the Pioneer Preaches of Indiana also makes it clear that the Christians saw themselves as in revolt against the Calvinist doctrine of predestination.

The lock at Coffee Creek was just one evidence of conflict. Among the members of the Church of Christ, organized by New and Carey Smith in Madison in 1832, was another elder, Jesse Mavity, who had taught school in the basement of the Masonic Hall along with his brother Henry. “Prior to the organization of the church, who had preached with great acceptance for the several denominations of the city, all of whom were liberal patrons of his school,” But because of Mavity affiliated with the Christians, when he changed his school to a high school, the subscribers withdrew. This account makes it sounds as if the Mavitys were set up for failure by those who urged the change in schools; another that the school was simply abandoned by opponents the new denomination.

Churches changed affiliations. The first Baptist Church in Indiana, the Silver Creek Baptist Church in Clark County, joined the Christians. Two New Light Churches (a dissident form of Presbyterianism), a church named Liberty near Kent and another another Liberty Church at Mud Lick (later called Bellview) became Christian bodies in the 1830s.

But one of the bitterest fights took place in Milton Township, where the newly founded Milton Church found itself subject to the divisive forces. It may not have been more bitter than elsewhere; but three accounts show that it must have been a heated discussion.

All of the accounts have some errors and they gloss over some of the pertinent points, partly because two were written from the viewpoint of the Christians and the other because it was a local history, whose main purpose wasn’t defining religious movements.

The Milton Baptist Church was founded in 1829 in Milton Township about two miles east of modern Manville. It was the first church that organized in and met in Milton Township.

It must have been subject to tension from the beginning for a History of Milton Township written sometime before 1908, probably by William Ryker, then president of the Jefferson County Historical Society, refers to the Manville Christian as growing out of a Manville Baptist Church. No such body every existed—it clearly grew out of Milton.

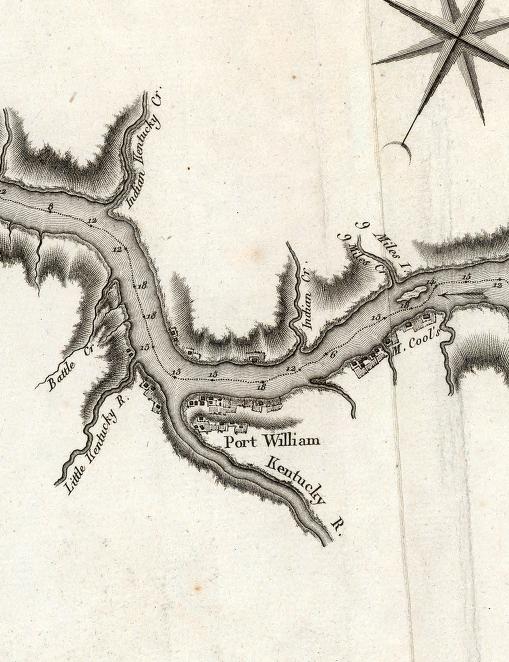

This account says the church had two ministers, Benjamin Levitt and Joseph Hankins, who were divided on practice, one for open communion, one for closed communion. Then Jacob Short, who had been one of the founders of the Indian-Kentuck Baptist Church, included Beverly Vawter to speak. Son of Baptist minister Philemon Vawter and nephew of Baptist minister Jesse Vawter, Beverly had gone over to the reformers and was a major force in Jefferson and Switzerland County. Hankins, who was the minister at Milton Baptist Church in the early 1830s gets no more mention in his role in the events. But Levitt was an important player.

A biographical sketch of Beverly Vawter, in the same volume that profiled New, said that in the summer of 1830 “he was invited to attend the monthly meeting of a Separate Baptist church near the forks of Indian Kentucky. Their preacher and elder was a man by the name of Levitt, who was bitterly opposed to what he was pleased to denominate Campbellism.”

After Vawter preached and four members confessed and were to be baptized, Levitt was requested to attend their immersion and refused with "No, sir, they are your converts—I will have nothing to do with them." At the next church meeting, it was clear Vawter had won. (The formality of the quotes attributed to Levitt sound like they were constructed in later years, fairly typical for writings of the era.)

The story concludes with “This was the origin of the Church of Christ, now* known as Milton

Church, which still yields the peaceable fruits of righteousness under the pastoral care of Charles Lanham.” This time, the error in church names goes the other way. Because Lanham was known to be a minister at Manville Christian Church, and given the location at the forks of the Indian-Kentuck, the new body was clearly Manville.

Important points are lost here. Levitt, a native of Rhode Island, represented a more liberal Baptist view in which the ministers were sometimes affiliated with the Free Will Baptists, sometimes with the Separate Baptists. The Free Wills formed several congregations in Ripley and Switzerland County, but none in Jefferson County (unless the Milton Church was temporarily a free will). The Separate Baptists had only the church at Center Grove in Shelby Township, which became the regular Hicks Baptist Church in 1894, while there were more in Switzerland and Ripley Counties. Both bodies were non-Calvinist and most congregations were decidedly anti-slavery. There may have been a regional split—a more educated Northeasterner against the home grown ministers. It’s likely there was a whole mix of issues.

In any event, important members of the Milton Church show up in records of the Manville church from its founding. John Lanham and William Yates, who were messengers from the Milton Church to the Coffee Creek Baptist Association in 1829, were members No 2. And No. 4 respectively on the Manville membership list and Jacob Short was No. 21. There are no dates on this list before member No. 36, but it’s possible these were all charter members. And they brought their families within them. The final word on the Hankins role was that they stayed with Milton. Joseph Hankins died in 1836 and the church disbanded, but it reformed with his children playing a major role.

The third account, again from the Christian side, was a letter written on April 7, 1834 and printed in the Christian Evangelist. Its language is pious, bordering on haughtiness.

Not naming the church, but noting its location on the Indian-Kentuck Creek, the writer reported, “We esteem the word of God as living and effective and since we got rid of the Babylonians, thirteen of fourteen have been added to our number. Seven of the old folks remain obdurate, two of them were elders and one a Rabbi.”

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment