Many

Even fewer know that his three brothers, George Cary Eggleston, Joseph W. Eggleston, and Miles Eggleston, born in Vevay, became Confederate soldiers with George writing a famed account called “A Rebel’s Recollection."

George Cary was a

It is surprising there weren't more Hoosier Rebels—the area had a large population that came from the South. Before the Civil War, the South was filled with visions of the lower

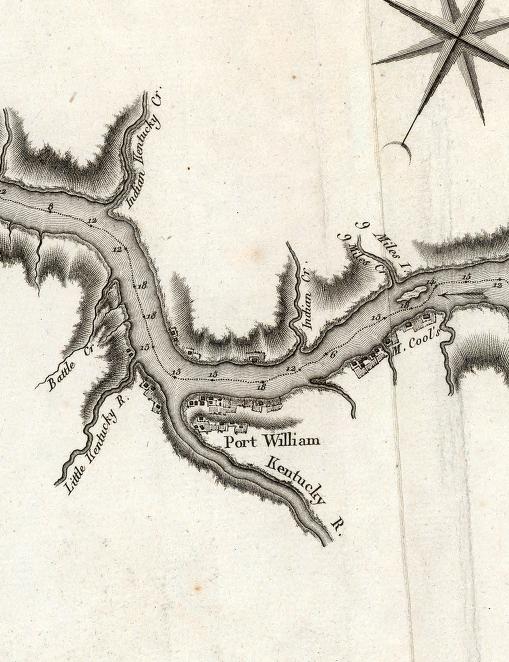

In fact, Morgan's raid was something of a community battle—many in the Fourth Kentucky Infantry lived just across the river. Carroll and

There were many divided families. James W. Quinn of

There were a number of "sort of"

A Prussian, Peter Charles Kyle, who came to Madison about 1844 and was educated there, helped form a Rebel unit Louisiana in 1861. Another member of the Fourth Kentucky, Minor Horton, left

One man, however, stands out as a Confederate who was born in

John Woodburn Shrewsbury took his name from his mother's father, John Woodburn, who helped found the Madison & Indianapolis Railroad. The son of Capt. Charles Shrewsbury whose home bears the family name, Wood, as he was called, was dedicated, but sickly, and served in several battles, although consumption (tuberculosis) often sidelined him. A Confederate account said Wood often served hospital duty because of his health.

The Shrewsburys were also a divided family because Charles participated in a rally in

There may have been more Rebels, but bragging about Confederate service was not safe in

In any event, Wood Shrewsbury survived the war, but not by much. A note in a